After arriving in Mexico City, bumbling through a discussion in Spanish with our transportation (my Spanish is terrible), and a 3.5 hour drive, Clayton and I arrived in a rainy Tlachichuca at the Museum/climbing hostel/residence of Dr Reyes and the Reyes family and headquarters of Servimont, whom we used for transportation and logistics. Thursday stay at the Servimont headquarters was excellent, we had the entire place to ourselves and dinner and breakfast were both 3 course meals cooked to order exclusively for us two. After procuring some last minute supplies and packing up just the gear we needed on the mountain, we set off in a decked out Dodge truck. For those reading for the trip report, the drive up to the Refugio Piedre Grande hut up on the mountain is pretty rough and i would recommend hiring one of the local guides, at the very minimum for transportation up to the hut, and you need about 40 pesos (as of 2019) each to get into the National Park.

Thursday afternoon we stepped into the hut for the first time, greeted by a crew from Wyoming who had just finished a fifth of tequila waiting out the rain

Thursday afternoon we stepped into the hut for the first time, greeted by a crew from Wyoming who had just finished a fifth of tequila waiting out the rain

"Hey, do you guys have any Tequila?? No... Cervesa?? No... Weed? No... Ok, we can still be friends"

I chose to go for a walk Thursday to get used to the thinner 14000 foot air that we would be living in for the next two days. Walking around the mid mountain area was pretty amazing, even though i didn't have the jaw dropping views we would have later in the week. The plant life in Mexico at 14000 feet and above the Mexican rain forest is vaguely familiar, but quite foreign at the same time. On the right: Home for the duration of our stay on the mountain, inside the Piedre Grande Hut

Friday morning we woke up early, at 12:30 am to be specific, as some other groups (a Mexican crew, some guys from Toronto, and they Wyomingites) got geared up for an ascent of the mountain. At 6 am Clayton and I woke up and started up just before sunrise for an acclimatization hike and to find the route through the infamous Labyrinth, supposedly a route-finding nightmare. As the sun rose over the now clear sky, we were greeted by the amazing expansive views of the Mexican high rain forest below, and the summit with freshly fallen snow up high. On our first ascent through the labyrinth, we followed the Wyoming crew's tracks up what we would discover was the incorrect route. Once we got up to our high point, ~16600 feet just below the glacier, it was clear where the actual path was. At about 11 am we turned back, ready for a hearty lunch and rest, prepping for our full ascent the following morning. I should note, i heard a lot about how difficult route finding through the labyrinth was. After finding the correct way and noting two key turns we needed to make, I thought the route was actually pretty straight forward (however the Canadians remarked that they would never have made it through without a guide). Maybe it is years of route finding training in Arizona, but the route is actually pretty easy to follow. The true route through does not follow the trail noted on most topographic maps (for the reason that will be noted later). We spent the rest of Friday resting and eating and went to bed at 6pm in anticipation of our 12:30 am wake up on Saturday for our summit push. Above left: Sunrise on the flanks of Pico de Orizaba. Below left: an aqueduct that serves as a sidewalk approach to the mountain from the Piedre Grande Hut.

View of the Labyrinth and Summit on our Acclimatization Day

The planned 12:30 am wake up call quickly became an 11:45 PM wake up instead. Unfortunately due to the close quarters in the hut, when one person gets up, everyone gets up. By 12:20 we were suited up and set off. One perk of going in a small, unguided group, is that we don't take a ton of time to get ready. We were the first group out by about a half hour.

Chatting with one of the guided groups, they remarked "oh, you two were the two headlamps we saw way up near the top??"

One of the biggest unsung praises of alpine climbing to me is the peace. Walking in the calm still of the night, under the moon and stars for 7 hours with the many small towns of rural mexico sprawling below you, that's an experience that words and pictures can't replicate. The night sky has an unbelievable clarity at such high altitudes and the stars and moon were visible with a clarity that i had never before experienced.

Above Left: Moonshine, Stars and whispy clouds at 4 am over the upper reaches of Pico de Orizaba.

Above right: Sunrise over the Glacier Gran Norte at 17,500 feet

Our run through the Labyrinth the day before was fruitful as we waltzed right through without any backtracking and by 5 am we were strapping on crampons, roped up and moving over snow and ice to the summit! Shortly after sunrise we were on top taking in the views and enjoying success.

Our run through the Labyrinth the day before was fruitful as we waltzed right through without any backtracking and by 5 am we were strapping on crampons, roped up and moving over snow and ice to the summit! Shortly after sunrise we were on top taking in the views and enjoying success.

Sunrise Walking up the Glacier

The Final bit of climbing on the right once we reached the crater of Pico de Orizaba

Looking down into the Orizaba Crater. Apparently there has been a high line set up over the crater at some point (we found high lining gear on the summit)

Looking out towards the Sea. The lower mountains visible are 10,000+ feet lower than we are at the moment.

Clayton and I on the Summit

On the way down we took a peak into the crevasses, there are only a few on the upper mountain and they are pretty easily identified and avoided. The sun came out and things got hot fast, by the time we got back off the glacier (after longingly watching our Wyoming brethren ski from the summit) i stripped down to only my Houdini shell. The daytime heat sublimated some snow, which super-saturated the air making for some interesting greenhouseing and fog at mid elevations on the peak. A few hours later we were back at the hut and cooking some mac and cheese to satiate our summit push hunger! After a brief pack and loading our gear into the 1962 dodge power wagon (amazing that Servimont is still using this as a daily driver up this rugged road, a testament to how well built it was!) we were back at the Servimont headquarters reveling in our success of a quick 48 hour acclimatization and ascent of the 3rd tallest peak in North America. Our route map is below. Really the key is to stay right immediately after the initial steep hill gaining 1000 feet, then go left directly into the labyrinth when the trail takes you up into it. If you can get this key left down, the rest of the route is pretty straight forward and simple to follow but glacier travel might be a bit more difficult if there has not been snow up there recently. If you are here just for the route description, this is where it ends.

Just before we leave, we finally get our first view of the mountain from Servimont HQ.

Our Route against the one on the topo on the left, and with a satellite ocerlay on the right. The route deviates from what is marked on the Topo because the glacier and snowfields do not reach as far down the mountain as they once did. Instead of climbing straight up the snow as mountaineers used to, we now have to navigate diagonally through the Labyrinth to get to the glacier. The key to navigation is to stay to the west of the labyrinth longer than you think is necessary (until the kink shown above) then go up a small hole and strike out diagonally through the labyrinth.

The main reason for my post this time was to express my amazement at the slow death of the main route on this amazing peak, and the two other peaks in Mexico that supposedly retain glaciers. Fair warning, i am stepping up on my soap box here for a bit.

While talking with Senior Reyes, who is perhaps one of the best sources of information on the subject, as his family has been up on the mountain for 5 generations or more and helped open the north side glacier route, the topic of climate change and changes on the mountain came up. As in most of the rest of the world, the glaciers of Mexico have been dramatically affected in the past 20 years. By some accounts, the three glaciers on Popocatepetl are gone all together (although in this case the disappearance has been sped by volcanic activity). In the case of the other two peaks, Ixta (which we did not visit) and Pico de Orizaba, the glaciers do not seem to have aged well. Senior Reyes sadly remarked that the glacier has been shrinking dramatically. This was readily apparent when i looked around at the various pictures and route maps that were hanging up throughout the gear room and climber lounge areas.

A recent Satellite Image of Pico de Orizaba

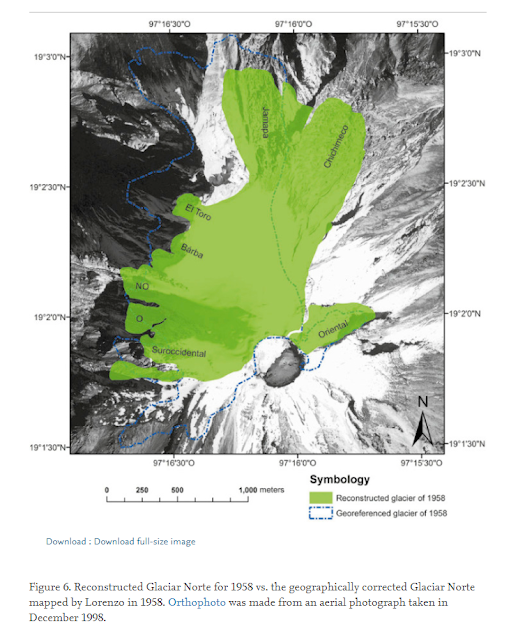

Glacier Mapping of Pico de Orizaba. Green: Rough map of glacial extent in 1958 over the image of glacial extent in 1998. Compare this to the above current state of the mountain. Image taken from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016716915000094#fig0030

Even 20 or so years ago, a ski descent of Pico de Orizaba would have been much more appetizing than it is now, adding almost 1000 vertical feet on to the descent you can do today. I wonder how the peak will withstand the next 20 years, and hope that the Reyes family can continue their business even as the peak continues to change dramatically.

Route pictures from Servimont with a rough position of the present day glacier levels drawn in.

I don't think an actual accounting of the glaciers in Mexico has been done in some time (where markers are placed and used to look for glacial movement, aka to determine if it is indeed still a glacier) but based on satellite pictures of Ixta against glacial mapping from 50 years ago, it looks like Ixta has lost its glaciers as well. The Gran Norte Glacier might be the only true glacier remaining in mexico.

This is the case all across North America really. I read recently that many of the glaciers in Grand Teton National park are being studied with glacial markers to see if there is still any glacial movement, of if these once rivers of ice have devolved into mere ice and permanent snow fields. I would assume the same is likely true for many of the glaciers in Colorado and California as well.

It will be a sad day when the glaciers of Mexico are gone, and with it the unique alpine climbing community that exists down there that revolve around the high elevations of Pico de Orizaba. The main difference of glacial loss here in Mexico versus in Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, Canada, Greenland, the Alps, and other places we traditionally associate with big mountains and endless expanses of ice is that all of these are arctic or near arctic places, known for their cold and snow; going to Mexico, a fairly tropical climate that everyone associates with beaches to climb a big ice covered peak and possibly ski off its summit is a unique experience. I hope that i do manage to ski off the peak before it turns into some small snowfields interspersed between mounds of volcanic ash and sand, remnants of what once was.

A great documentary i saw a while back looking at glacial ice loss in the more Arctic regions of North America, Chasing Ice, is a must watch for anyone curious or interested in the subject.

Also, here are some pictures of the crazy and vibrant plant life at 14-15,000ft down in mexico:

Some crazy variant of thistle that looks like purple eyeballs looking at you

Probably the most vibrant Paintbrush i have ever seen

Weird black cobb flowers (i have no idea what this is called

Something that resembles an air plant when young and grows into this thing.